The Black Vulture

Conservation Status: Least Concern

Appearance

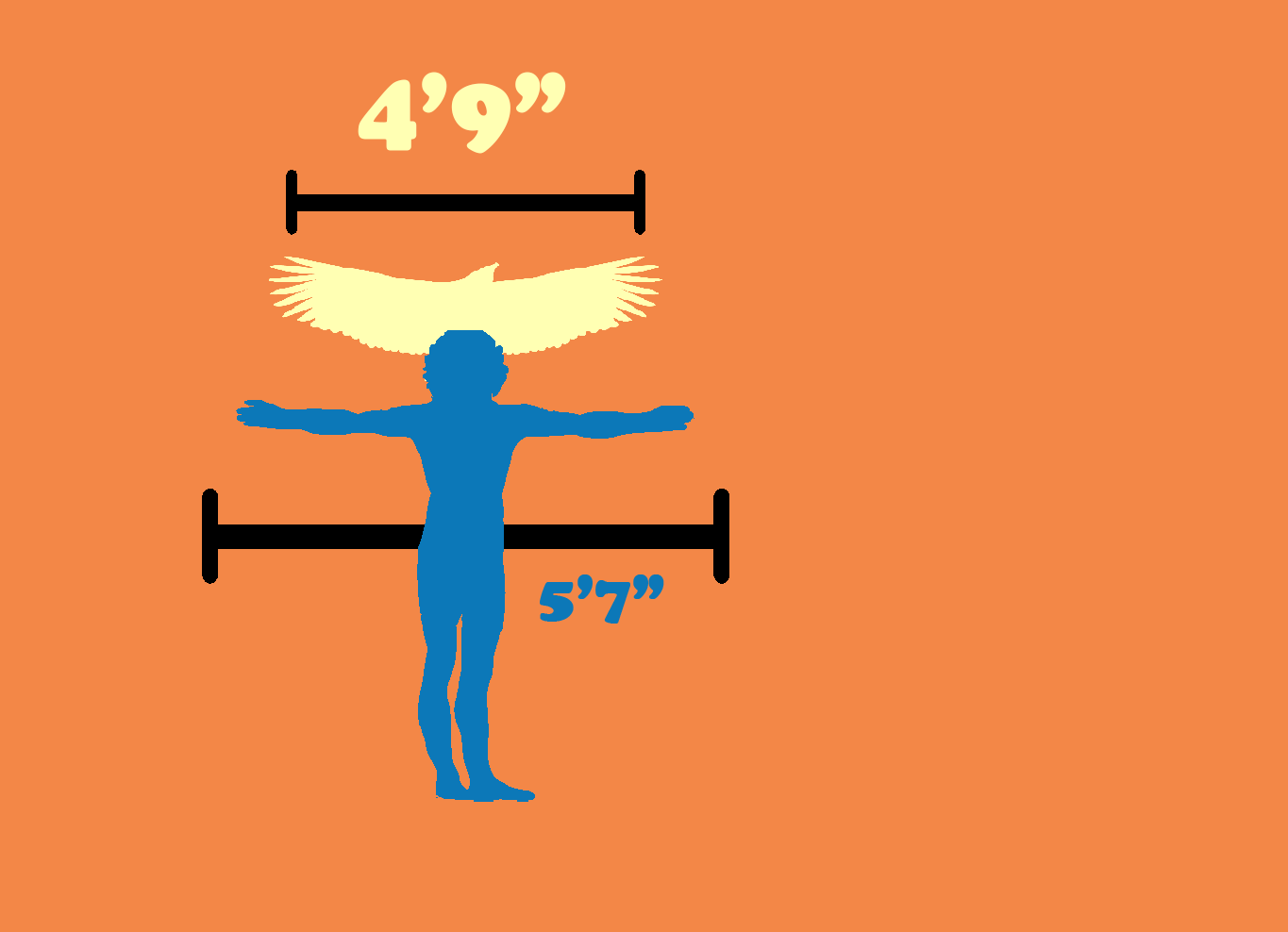

With wingspans that can reach 1.5 meters, or 4 feet and 9 inches, Black Vultures are large birds, but relatively smaller vultures - also weighing (at most) 6.6 pounds, or 3 kilograms. Black Vultures have even, glossy black plumage, with featherless, wrinkly dark-gray heads and necks; and in flight, the tips of their wings take a whiter, more silver, color. Their legs also take a more light gray, almost white, coloration. Black Vultures are stocky birds, with short and broad tail and wings - making them easy to differentiate from the similar Turkey Vulture.

Range

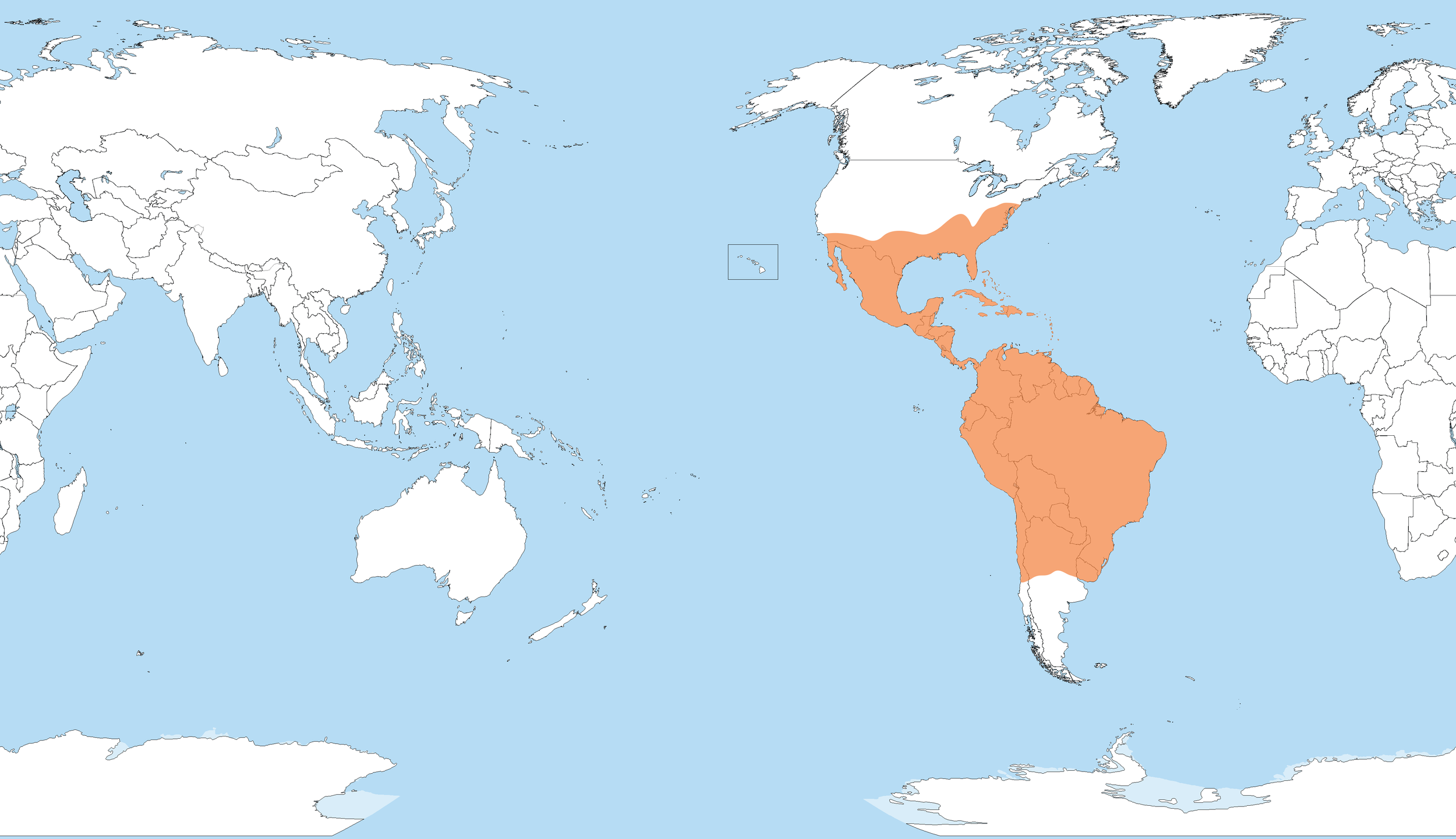

The range of the Black Vulture is huge - rivaled in the Americas only by the Turkey Vulture. It resides as far north as the Southern US, and as far south as Central Chile, and some have even been found in the Caribbean islands. Typically, despite the Turkey Vulture having a bigger range, Black Vultures are thought to be the most common birds of prey in the Americas

Blank map of world originally from Wikimedia, before adding approximate vulture range. Some Rights Reserved.

Feeding

Black Vultures can be found just about anywhere in their range, except for in areas with dense forests. The Black Vulture is one bird that has thrived from urbanization, being most often found near dumps and towns. When eating, it can be found both alone and in a large flock. Their food sources are incredibly diverse, ranging from; monkey carcasses, coyote carcasses, cattle carcasses; to fruits and vegetables; to assorted animal excrement; to turtle eggs. When it comes to carrion, they will typically rely on other vultures with a better sense of smell to find the carcass, like Turkey or the Yellow-Headed Vultures, to lead them to carrion, but can also identify carcasses themselves through sight. Despite them sometimes relying on other vultures for foraging, they have been observed to be dominant and aggressive over their larger counterparts - especially so when they are in groups of over 50.

Image courtesy of the John James Audubon Center at Mill Grove, Montgomery County Audubon Collection, and Zebra Publishing.

Other Ecological Notes

The Black Vulture is one of few vultures that will prey on animals - and due to its smaller size, typically small mammals, birds, and reptiles; and sometimes domestic calves and lambs. This often puts it in contention with ranchers that want to avoid Black Vultures preying on newborn livestock. That being said, Black Vultures are still incredibly important to ecosystems, particularly in the modern, urbanized world. Due to them eating carcasses and fecal matter, particularly at dumpsters and near towns. This prevents high density areas from being over-run with disease.

One fun note is that Black Vultures have been observed to remove and eat ticks off of Capybaras and Tapirs. Check out the video below for reference!

Video courtesy of Fernando Perez Piedrabuena, an ecological and biology researcher from Uruguay.

Breeding

The time at which a Black Vulture breeds varies from place to place - typically varying with latitude. As such, breeding for them technically occurs year round throughout the Americas - but breeding seasons will only last some months for individual populations in different regions. Courtship during these times can include ground and in-flight rituals. Upon breeding, nesting areas are settled, but not nests - Black Vultures do not use nests or nesting material, and rather prefer to decorate the areas with bits of brightly colored plastic, glass shards, or metal items like bottle caps. Both parents will take turns incubating eggs - typically one to three per season - for about a little over a month, and hatchlings will remain in nests until they can fly - typically after three and a half months. Few animals will attempt to prey on the chicks at this time, as Black Vultures can be incredibly aggressive, but some eagle species will prey on chicks and adults. It can be hard to tell juveniles apart from adults - but juveniles will typically have duller wing feathers and smoother, darker heads.

Images above originally from Flickr, taken by Dennis Church (left) and Andrew Cannizzaro (right). Some Rights Reserved - left image, right image.

Conservation

Black Vultures have a status of Least Concern - and are generally doing well in adapting to the modern, urban world. As mentioned above, they tend to be in contention with cattle ranchers, as they can prey on cattle and lamb. In the US however, it is illegal to harm or kill a Black Vulture. It also receives legal protection in Mexico and Canada. One place that is a major threat for individual Black Vultures - not populations as a whole - is an airport. Black Vultures coming together in large numbers in dumps near airplanes can result in their endangerment, as well as that of an airplane.

Image above originally from Flickr, taken by Scotty Emerle. Some Rights Reserved.

Cultural Impact

In the modern day, Black Vultures have appeared as icons on postage stamps - for Nicaragua in 1994, and Suriname in 1990. It is also cited in some news articles as a modern icon of great importance in Lima, Peru, where they act as literal clean up crew for many of the illegal dumps in impoverished areas of the city.

Older cultural references include an appearance in the Mayan Codices. Just as in the modern day, Black Vultures are not painted in the best light here, with them being featured in hieroglyphs as birds of prey, birds of death, and as birds that attack humans.

Pictured above are a clay whistle (top left) and two Mayan hieroglyphs, all depicting a Black Vulture. All images originate from this article by Tozzer and Allen (1910).

Social Media

Black Vultures have recently become slight stars in social media. Recently, Bash the Vulture, a Black Vulture that has become an avian ambassador at the American Eagle Foundation due to its un-releasable status, was featured in a GeoBeats Animals Youtube video that has amassed nearly 800,000 views!

A couple of videos of Black Vultures flying alongside paragliders have also made the rounds on social media, with both videos featuring a Black Vulture that lands on the paraglider structure - seemingly curious and content.

Image above originally from Flickr, taken by Luis Alejandro Bernal Romero. Some Rights Reserved.

References

-

All About Birds: Black Vulture. 2003. Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

BirdLife International. 2016. Coragyps atratus. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

Birds Protected by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. 2007. US Fish & Wildlife Service.

Black Vulture, Life History, All About Birds. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. allaboutbirds.org

Coleman, J. S. and Fraser, J.D. 1986. Predation on black and turkey vultures. Wilson Bulletin. p. 98.

Coulson JO, Rondeau E, Caravaca M. 2018. Yellow-headed Caracara and Black Vulture Cleaning Baird's Tapir. Journal of Raptor Research. 52 (1): 104–107.

Drowning in rubbish, Lima sends out the vultures with GoPros. The Guardian.

Elliott, Glen. Coragyps atratus (black vulture). Animaldiversity.org.

Fergus, Charles. 2003. Wildlife of Virginia and Maryland Washington D.C. Stackpole Books. p. 172.

Ferguson-Lees, J. & David A. Christie. 2001. Raptors of the World. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 309.

Game and Wild Birds: Preservation. US Code Collection. Cornell Law School.

Nature Guides. Enature.com. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016.

Migratory Bird Treaty Act. US Code Collection. Cornell Law School.

Reader's Digest, ed. 2005. Book Of North American Birds. Reader's Digest. p. 11.

Sazima, Ivan. 2007. Unexpected cleaners: black vultures (Coragyps atratus) remove debris, ticks, and peck at sores of capybaras (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris), with an overview of tick-removing birds in Brazil. Rev. Bras. Ornitol. 15 (1): 417–426.

Tozzer, Alfred Marston and Glover Morrill Allen. 1910. Animal Figures in the Maya Codices. Harvard University.